Three hundred and sixty-four days. From the launch of 忍Shinobi on the Playstation 2 to the release of its sequel. This was the time allotted to the development team of Sega WOW to produce the next entry in this long running series. One day less than a whole year for concepting, designing, developing, testing, adjusting, marketing, production, shipping and releasing the game.

It could work. Many studios produced some of their best work under pressure, like God Hand, Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance, Halo 2 and P.N.03. All unique games with short development times, finding joy in jank and having the tight deadline force the developer to make quick and hard calls.

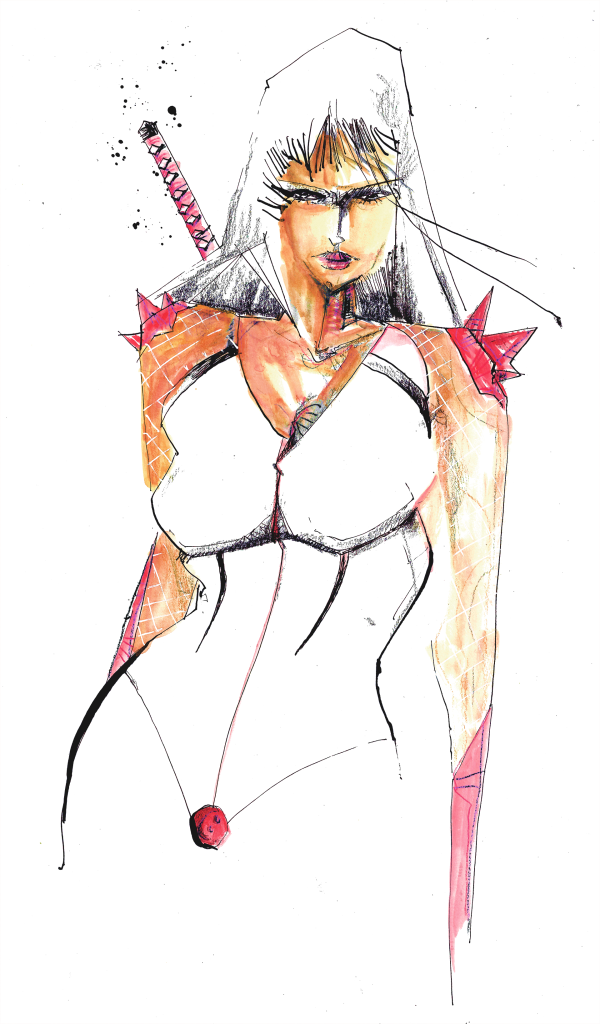

Sega WOW’s first call was that the sequel would build upon the groundwork 忍Shinobi had laid i.e its engine and gameplay. The first change however was also already in the works; it would be the first title in the series to star a female lead. Hibana, a sexy ninja operative sporting a white latex suit with twin scarfs was to replace Hotsuma and as such they saw fit to also change the series’s title. With 忍Shinobi being Japanese for ‘male ninja’, they went for ‘female ninja’:

There are many reasons to make a sequel. Within videogames it can be simply to increase profits, but also to continue a story, evolve upon the gameplay or simply to do what was done before but better. Within the latter methodology there are two ways to go about it. You can focus, as was often the case at rival company Capcom, to eliminate the negatives. Or, you can focus on what’s good and make that even better, which Shinji Mikami, of Resident Evil fame, in interviews notes as the “warts and all” approach.

For a title under such tight pressure, Sega WOW didn’t have the time to reinvent the wheel. So it was either “eliminating negatives” or “warts and all”. Playing 忍Kunoichi today (called 忍Nightshade in the west) it would quickly become apparent which path they chose.

Starting off, the basic premise is unchanged. Like Hotsuma before her, Hibana can double jump, climb on walls, throw stunning kunai and perform aerial dashes, supplemented by regular and charged attacks (dubbed ‘stealth attacks’ in this game). The name of the game is still the Tate system. Starting a countdown when Hibana kills the first enemy, this timer fills up a tad with each kill while also making her stronger. Like in 忍Shinobi, the goal is then to keep the chain going while getting more and more powerful, eventually killing everything in a single blow until the fight ends and the counter resets.

It was this foundation that 忍Shinobi lived off of and built its 8 missions around. To give an idea of what Sega WOW would focus on in the sequel: 忍Kunoichi features 13 stages instead.

Throughout those stages, Hibana will also use new tools. No longer does the cursed blade Akujiki drain your life, instead using directional inputs Hibana can swap between her own katana Utsushiyo (現世) and her short Futaba blades ( 二羽). Compared to regular attacks, the Futaba Blades deal less damage and have less range but in return charge your chakra-meter which is needed for the aforementioned stealth-attacks for massive damage.

While she can still kick enemies to stagger them, she can now also do a launching attack and then a falling kick for an area-of-effect shockwave, adding a new twist to a familiar move.

To compensate for these new moves, enemies were changed accordingly. While their general patterns and mobility remained the same, namely that they exist more to break your Tate-chain than outright kill you, certain monsters now have extra armour plating that first needs to be removed through kicks. Fights are also far larger in size, with platforming taking more of a back seat to the 20 to sometimes 100 enemies spawning in a fight, usually in groups of five to ten at once. To make this workable, arenas are more flat, with only the occasional wall to climb but not a ton of pitfalls.

Let it be clear that Sega WOW had made their choice. With the deadline limitations they would aim to improve on what was there in the original, ‘warts and all’. This consisted of the Tate system and the combat surrounding it. As such, elements like platforming and exploration would take a back seat.

These new combat options let fights play out in different ways than before. No longer is Hibana limited by a two-dash limit now that she can also do an aerial kick to propel her even further. With fights taking place on more even ground, positioning is less of a problem. It allows you to dash from foe to foe, hitting their weak spot with an occasional set of kicks to remove armour before making the next killing blow. With how large the fights get, the feeling can be exhilarating as you swap between the moves and dash across the room hunting for the next foe before the timer runs dry for that sweet final-kill animation.

Compare this to 忍Shinobi, where a fight was more against a constantly ticking clock of doom while dancing around enemies and looking for weak points. Once opened up, a killchain would start with your blood boiling as the timer on the Tate started counting down rapidly; all while navigating areas with more walls than floors, a single drop spelling your demise.

Without this ticking clock of doom, it is understandable that 忍Kunoichi put a bigger focus on the completion of larger chains to replace the thrill to survive for one of empowerment.

However, the difference is that the soul draining Akujiki offered a gameplay reward; it kept you alive, while the new supplement is more a fancy visual with some extra points. Points which offer nary a reward, and the Tate chains – no matter how great and fantastically visualised – run dry after the eight hours it would take to beat the game.

Because of this lacking thrill and aforementioned flattening of the level geometry, 忍Kunoichi’s fights can start to blend together fast. Though you now press a few more buttons in the process and kick armoured foes before slicing them, the basic gameplay loop is still unchanged while missing some other elements.

A good example of this is the aforementioned kick. In 忍Shinobi, the kick was a multipurpose tool used for stunning enemies so you could dash behind them for a killing strike, to kick them off ledges, stunlock bosses or to stagger an enemy if your kunai had ran out. In 忍Kunoichi, if you see an enemy with armour, you kick them. If you see a group of armoured enemies, you do the ground-pound kick. It’s a very binary system that, while having more options in total, offers less freedom and versatility in its limited moveset by giving you such a clearly defined usage of the ability.

You could say the same for the light and heavy attacks which, while cool, tend to overcomplicate what was already there. Or how the new ‘stealth-attack’ is now a homing ranged attack, instead of a hard-to-time charged slash.

Both design choices of course have their own up- and downsides; the charged slash from 忍Shinobi could always be used if a Tate was in progress while 忍Kunoichi’s stealth-attack needs a filled up chakra-meter to function, so balancing is definitely an issue. It should be clear that these elements wouldn’t have been so criticised here had this game been the first in the series and 忍Shinobi its sequel.

By themselves a lot of these mechanics still work interestingly well. From the (returning) ranking system, three unlockable characters, post-game challenge missions, a ton of collectibles hidden away in the levels to bonus coins to collect for a higher-score, a survival mode, and more – 忍Kunoichi still is that type of game we can only call ‘typically playstation 2’ in the best sense of the word.

Regardless of these comparisons there are moments when 忍Kunoichi’s combat does fully come together, namely in its vehicle sections. Here Hibana must jump from a speeding boat to boat, dashing between enemies using all her tools while hopping on to the next one. The concept is reused a few times; sometimes you’re on a truck on a highway and the first mission has you battling on a flying stealth bomber. Not only are these settings visually stunning, their deadly pits bring back the feeling of danger sorely lacking in the rest of the game. Dashing from foe to foe, using all your abilities, with the knowledge that one wrong button means Hibana falls to her doom is a tense experience, all the more pleasurable when the final Tate animation plays, rewarding your excellence.

It is in these moments that, pardon the frequent comparisons, 忍Kunoichi captures the brilliance of 忍Shinobi and at times even surpasses it. As such though it also captures its flaws. With the team’s desire to focus more on what worked and improve on that, flaws like the lacklustre boss fights – which still have you basically stand around and wait until they summon minions for you to kill to power up – are still mechanically unchanged.

The lack of combat variety is also still present, though the game tries to alleviate this a tad by making nearly all the fights optional, with of course the downside that you’ll have less chakra and kunai for the inevitable bossfight near the end. If you don’t care about your rank near the end, you can dash past nearly every fight until the end.

These are solutions that feel more like quick fixes for problems that weren’t that important, or in other cases additions to elements that didn’t need additions. Despite aiming to do more with the established formula, 忍Kunoichi manages to do less with more, while 忍Shinobi did more with less; a painful conclusion. Perhaps it didn’t know what made it so potent of a game, or didn’t learn its lesson properly.

Ironically, many of the games’ flaws are removed should a player have a memory-card with a 忍Shinobi save file, unlocking Hotsuma as a playable character upon completion of the game. In terms of gameplay he’s identical to before, though a bit supercharged. His charge attack now uses chakra as well but instead he starts with a full bar that drains constantly and refills when enemies are killed, simulating the life draining effect from the previous game. Other than that, he’s the same, even lacking the newly added light and heavy attacks or dash-kick, making 忍Kunoichi suddenly play a lot more like an expansion pack to 忍Shinobi.

Even with this change though, the lower emphasis on level geometry and elevation makes fights quickly feel dull and repetitive, and more about empowerment than pressure, regardless what Hotsuma brings to the table.

Looking back at 忍Shinobi, one cannot blame the developers for missing the point of what made the previous game so interesting. While the platforming and life-drain were indeed a point in its design, every writer, both at the time and today – myself included – always talked about its Tate system, not the platforming which was always a byline at best. It is logical to assume the developers saw this and expanded on that system as they have done.

Playing 忍Kunoichi brings to light that 忍Shinobi is more than just that; it was great due to its combination of platforming, time-pressure and Tate system and how they all worked together to bring a memorable and tense experience. You don’t notice how important something is to the overall experience until it is gone.

Let it be said that what was good in 忍Shinobi is still good in 忍Kunoichi and sometimes even better. Movement is a joy and the expanded moveset will at times see you zip through entire stages, dancing from one enemy to the next. Its faults lay into the undeniable comparisons to what came before. Where it sought to expand and improve on what 忍Shinobi did, it only added dressing where it wasn’t needed and as a result removed elements that made it the game it was. As a result, it’s a great game to start with, but playing 忍Shinobi afterwards might make you feel that it is 忍Kunoichi’s sequel, instead of the other way around. Warts and all.

鑒 reflection style 鑒

In this short section I reflect on the article from my own viewpoints as a gamer and lover of the genre instead of a critic.

忍Kunoichi is a title I mostly feel regret from. As a teenager I distinctly remember watching reviews of it on a dutch review show called “Gammo”, a review they often repeated due to the attractive femme fatal. Once I had played 忍Shinobi, nearly a decade later, I was entranced by the idea of a faster, more lean sequel that would iron out the chinks of the first game.

Because I really enjoyed 忍Shinobi. It is one of my personal favourite action games, up there with behemoths like Ninja Gaiden II, Vanquish and Zone of the Enders 2nd Runner. Like most of my favourites though, it is a diamond in the rough that could have done with a few more months in the oven, and its sequel would’ve been perfect for this. When I booted up my used copy of 忍Kunoichi, finally, after having hunted for a disc for months, it was even better than I had dreamed.

The first stage, set on the stealth bomber, was a dream. It was fluid, it was action packed, within minutes I was killing enemies and fighting a boss to a great soundtrack. The second stage thrilled me even more with its industrial music and disgusting boss fights. Then, around the third stage, I started getting bored, and I wasn’t quite sure why. Around the fourth stage I did something I never do; I quit and didn’t touch the game for a few years, until I vowed to beat it and give it the attention I felt it deserved.

But I couldn’t, and dropped it again. I finally beat it 2 hours before my honeymoon flight to Greece last year (2021). It took great energy to pick the game up afterwards, which I only did for this review.

I think it’s a good game, and had it come before 忍Shinobi I’d have thought it was a fun and interesting title, with a fantastic and masterful sequel. Instead, it feels like many steps back mechanically, while going for cheap thrills in terms of cool visuals and fancy Tate-animations.

It is no surprise to me that the series went back to its 2d roots after this game. Though it is a shame, as there’s definitely potential to the 3d 忍Shinobi series. It’s just really hard to make a sequel to a game that’s all about simple design. Even the slightest addition or change can ruin it all.

斬 postscript notes 斬

- The game is directed by Masahide Kobayashi, former planner of 忍Shinobi 1 and 2, who had brief directorial roles in games like Knuckles’ Chaotix in the past. Former director Toru Shimizu was busy working on Skies of Arcadia’s re-release on the Gamecube. Meanwhile Masahiro Kumono still retained the role of Chief/Senior Director of 忍Shinobi for the PS2;

- A minor thread throughout the article is that the team didn’t learn their lesson. You could say they didn’t even learn the lesson in terms of release-date. Where 忍Shinobi’s innovative release was overshadowed by Devil May Cry, 忍Kunoichi would barely get a minute in the spotlight with Ninja Gaiden’s demo-disc hitting the streets only a month later, and fully releasing the month after that, leaving Hibana in the dark;

- Special mention should go to the song Monster Freak (Track 18 on the official soundtrack), which plays during the stage-11 boss;

- A small side note should be made of the fact that there’s also a risque video game called Nightshade on the Nintendo Switch and Steam, which made many search results come up negative, while also giving my editor false hopes that I’d finally shown my true self;

- It should be noted that the game was made by Sega WOW, which is simply a renamed Overworks Ltd. Hence, the games are made by the same studio, just using different names, a fact that seems missed in many discussions relating to the games.

- This is the first article where I made custom artwork, hope people like it!

源 sources 源

“Shinji Mikami – 2000 Developer Interview.” shmuplations.com, 27 March 2022, https://shmuplations.com/shinjimikami/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

In my view, Shinobi (2002) was “great” and Nightshade was “good”.

I really enjoy both games, but it feels like Shinobi had better balance. Nightshade has differences in mechanics, but perhaps they didn’t have enough time to fine tune them.

At least some people prefer it just for stylistic differences, though 🙂

Funky music and more “modern” vibes, yeah.

Cheers!

I really liked the OST in Kunoichi, especially that of the later lady boss (forgot her name tbh). Track was called: Monster Freak.

Super cool theme!