Imagine walking through an arcade-hall in the 80’s. The smell of cigarettes, strobing lights … and a game you’ve been playing every day after your daily routine has been lived. You know this game inside out. Every trick, hidden weakness, shortcut and glitch. Where some might need a month’s salary in quarters to see its end, you’d need only a single coin.

As you play, a crowd forms. You decide to show off. “I had no idea you could do that”, says someone in the crowd. As you reach one of the hardest bosses that has eaten many a coin, you decide to show them you can actually kill it in a single hit using a specific tactic. A kid next to you gasps. You feel elated.

Now shift this situation to home. It’s the 2000’s. Same scenario, a game you’ve mastered and know inside out. As you play however, there is no audience. Only yourself and perhaps your sibling, parent or spouse off in the distance, half gazing at the television set.

These experiences aren’t even close to comparable and it is with this notion that arcade-fan Hideki Kamiya aimed to build Resident Evil 4. A construction that took a life of its own and, upon request of his mentor, took the shape of an entirely new intellectual property: Devil May Cry.

First released August 2001, Devil May Cry, デビル メイ クライ, needs no introduction. One of the longest lasting franchises in the action genre; the game that brought the genre to the attention of many … and also the game where this very site gets its namesake from.

But how did it get there, how did it change over the years and what stayed the same? Let’s dive in.

Sporting a laid-back protagonist and a ranking system based on how ‘stylish’ players performed, at its core Devil May Cry aims to bring that feeling of the arcade-crowd to the couch at home. It wants you to show off.

At its center stands former to-be Resident Evil protagonist Tony Redgrave-Spencer, now simply known as Dante. Jumping and rolling out of danger, wielding a gun and melee weapon at the same time and the ability to swap them around for others like grenade launchers and Ifrit’s flaming fists to give him a plethora of options. Add the option to juggle foes and the patented Devil Trigger that temporarily increases his speed and strength, while also giving him access to unique moves, and you’ve got a playable character that can really fight both up-close and at range. This gives the combat a very dynamic feel.

Around him stand the enemies, some of whom die to a single stroke in their spine, while others allow players to stand on their spike-attack for an easy taunt. Some dance around Dante attacking aggressively, while others stalk him, hoping for him to make a mistake. Each enemy has his own little tricks in how they interact with Dante and how he can interact with them in turn. Bosses are equally detailed with some having hidden weaknesses for an instant-kill while others have numerous tactics to approach them with.

By giving enemies these unique quirks to exploit while also offering plentiful combat options to Dante himself, Devil May Cry readily promotes creativity. And by making enemies difficult, bosses challenging and traps devious said creativity feels earned and rewarding.

Below that arcadey surface some of the original Resident Evil DNA remained however. The static-camera angles, tank-controls, slower pace, tight corridors, a lot of retreading ground and repeat boss fights and even a boss that summons already conquered bosses can hold the game back at times. Technical shortcomings, such as a lengthy animation or menu usage being required to swap weapons mid-battle are also present and slow the combat down significantly.

Despite these shortcomings however, looking at the game’s strengths, each separate element isn’t a stand-out perse. Juggles, ranking systems, detailed enemies and Devil Trigger to name a few were all done before in other 3D games like Rising Zan: The Samurai Gunman (ライジング ザン ザ・サムライガンマン) or Dynamite Deka (ダイナマイト刑事 – also known as Die Hard Arcade). They were even present in other 2D arcade fans of yore, be it beat em ups like Dungeons & Dragons: Shadow over Mystara, fighting games like Xmen VS Street Fighter or a combination of the two like Red Earth; some of which Kamiya enjoyed in the arcade himself.

The key operator here being “separate” – Devil May Cry combined them into a new whole on its Playstation 2 home which led to its critical-, fan- and financial success.

This combining of elements can be seen in juggles for example. Aside from dealing good damage and making you safer in the air, they also play into the style-system by giving players a higher rank. Besides bragging rights these ranks hand out more upgrade-orbs, which in turn allows for more creativity through unlocked moves. In addition, players could use those orbs to buy powerful items whose use made the game a lot easier but in turn sacrificed rank.

Even minor elements like taunting played multiple purposes, namely preventing the style-meter from degrading by inactivity while also replenishing Devil Trigger meter which could in turn be used for more offensive or stylish play.

This interplay of all its systems is what truly made Devil May Cry shine and the choices it offered the player, this ‘freedom of play’, has been at the center of the series ever since.

It has been like that in the broadest sense of the word: freedom in playstyle, freedom in challenge, freedom in expression and more. Don’t care about rank? Focus on an efficient playstyle with item usage. It would optimize the game, while players that did focus on rank found an equally interesting puzzle to solve. This appeal was compounded by the game’s higher difficulty settings like Dante Must Die, which were built on the base of Normal and added remixed enemy encounters as well as giving enemies access to their own Devil Trigger for boosted durability – a difficulty mode that Kamiya himself never was able to beat.

All these elements saw the series grow not just as a franchise but also as its own little culture. With forums like Gamefaqs going live just two years prior, it saw a tiny community form in the middle, paired with its own fan communities like Phantombabies and the later Devilmaycry.org, where players like Joch1 would appear on the scene and would look deeper into its systems.

Devil May Cry’s success would also see the rise of games looking to cash in on the series’ booming popularity, making little changes to the formula to make it more their own. A bigger melee focus, a badder ranged focus, some swapped the style-meter for a hit-counter while others aimed to give a twist on the formula, perhaps through an emphasis on mobility or having summoned monsters do the work for you.

Regardless of their success or how they changed and improved on the formula laid out, it was clear that Devil May Cry had left a mark on the industry and everyone who played it!

This impact wasn’t expected by Capcom however and understandably so. A title that spun out of another that was nearing development hell, eventually built in around a year, with a small original printing, becoming one of the most successful and best reviewed games of Capcom’s fiscal year? No one saw it coming.

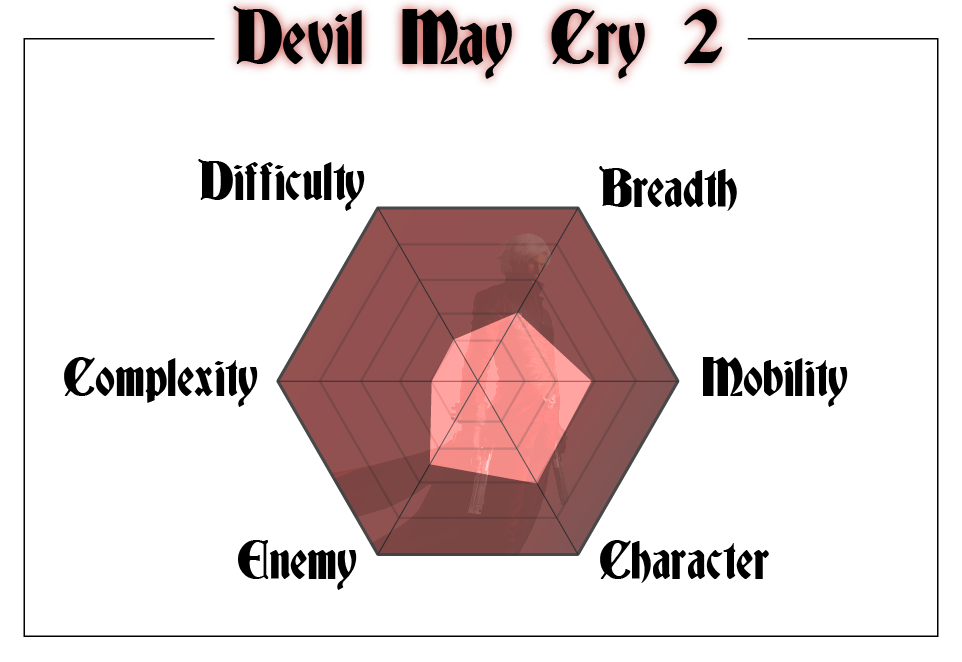

Quick to capitalize upon this, development on a sequel started, planned for a release less than 17 months after the original game’s release. A tall order. Where would one start on such an endeavour? Since the game had only had a single entry, it was understandably hard to nail down what defined Devil May Cry as an upcoming series. So let’s take a little look into its future and note down what could be considered the game’s six core elements.

| Challenge | the difficulty of the game, its enemies, aggression of foes etc. |

| Complexity | the complexity of inputs and difficulty of controlling the protagonist. |

| Enemy depth | the design of enemy movesets and how they play into the game’s other systems and its protagonist. |

| Character depth | the design of the protagonist’s moveset and its options. |

| Mobility | the mobility on offer for the protagonist, usually in tandem with Character depth and complexity. |

| Breadth | the amount of available content and playable characters. |

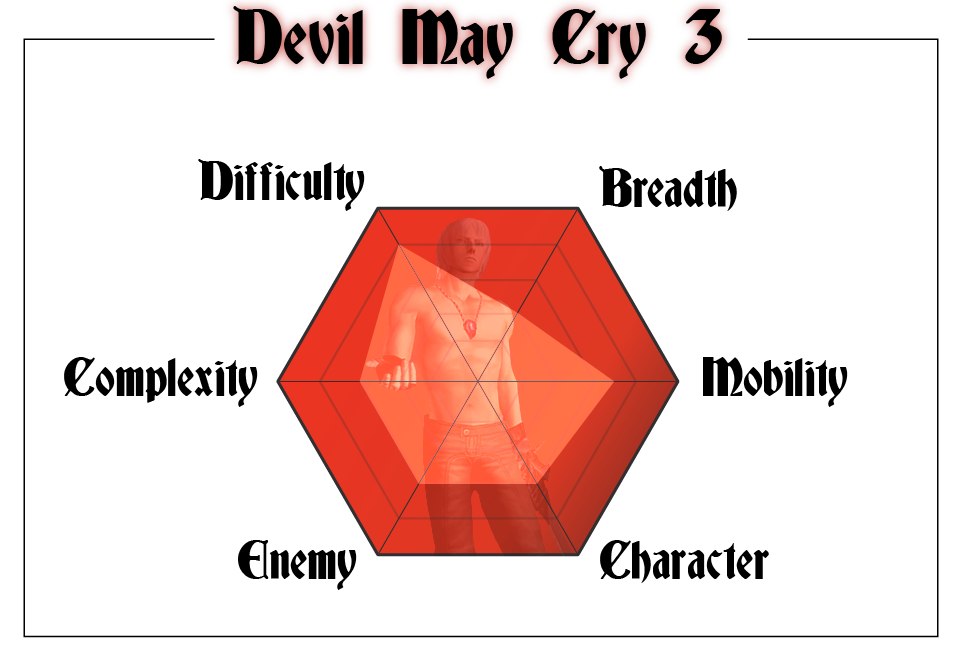

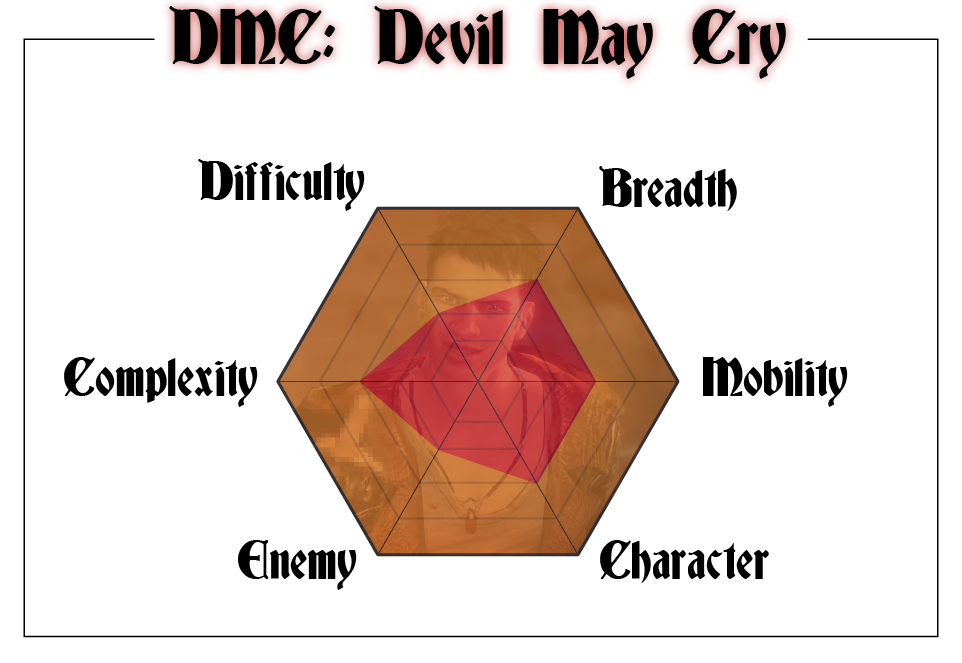

Now it should be noted, some of these elements are more important to some than others and are by no means indicative of any game’s quality. That said we can use them to gauge changes made to the games throughout the years and their direction. For example, put into a diagram, Devil May Cry’s first iteration could be presented as such:

With the peaks indicating the element being at the series’s highest point up until its latest release, you can see that Devil May Cry 1 shines in its enemy design and challenge. On the flip side, its character is a tad simplistic in terms of options and mobility.

NOTE: this diagram is of course only for illustration purposes of a game’s features compared to the rest of the series, and is by no means close to a scientific researched diagram. Nor are the terms of what depth ‘mean’ set in stone, but we’ll use these as they are now throughout the article.

One could say that the way these elements were directed at the time was the ‘core’ of the series.

Now, trying to capitalize on the unexpected popularity of Devil May Cry, Capcom rushed production of a second title, leading to a struggling development without even the original team being involved. Devil May Cry 2’s development was later heralded to be saved by director Hideaki Itsuno. Coming from fighting games like Capcom vs SNK 2 and Power Stone, he was brought in near the end to put the game’s development back on track and have it ship on time. With the title barely having a functioning Stinger move, let alone enemies, characters or environments, a challenge awaited him. With just a few months left, the game was shipped in a state as well as could be expected.

Despite these production setbacks, Devil May Cry 2’s launch in january 2003 aimed to be bigger and better. Featuring large city-scape levels, a more mobile Dante who could now wall run and access new Devil Trigger modes while also featuring two other playable characters. It also introduced being able to swap between ranged weapons with a tap of the button instead of through a menu.

It was a change that led to ranged weapons being very potent, as they were now high damage tools that also gave solid stylepoint, with large areas allowing players to stay at range. A combination of elements that saw melee become less dominant.

While there was certainly enjoyment to be found by rushing bosses down with good meter management and dodges, it skewed the ranged & melee balance that made the original so potent. Little details were overlooked, fights felt less constructed and more slapped together, enemies had less moves and even items no longer punished rank as much, leading many SS-rank runs being filled with item-abuse for a lot of meter.

In retrospect, it stands out not because it is bad as many would say, but because it is easy for the player to make it boring.

If we put Devil May Cry 2 in the diagram, we’ll see it is jumping around a lot compared to the core laid out by its predecessor. Complexity is down, though Breadth is slightly higher due to Trish and Lucia’s inclusions. Mobility is way up, same with Character. This is thanks to the added combat options Dante now has in terms of wallruns, Devil Trigger’s added combat options, the low-HP Majin Form, weapon switching and more – regardless of their balance, potency or motivation to use.

Due to its shaky qualities, Devil May Cry 2 became infamous for its mediocre quality. Not wanting his legacy of the series being “The man who killed a series before it could flourish”, Itsuno set out for revenge; paving the way for Devil May Cry 3: Dante’s Awakening.

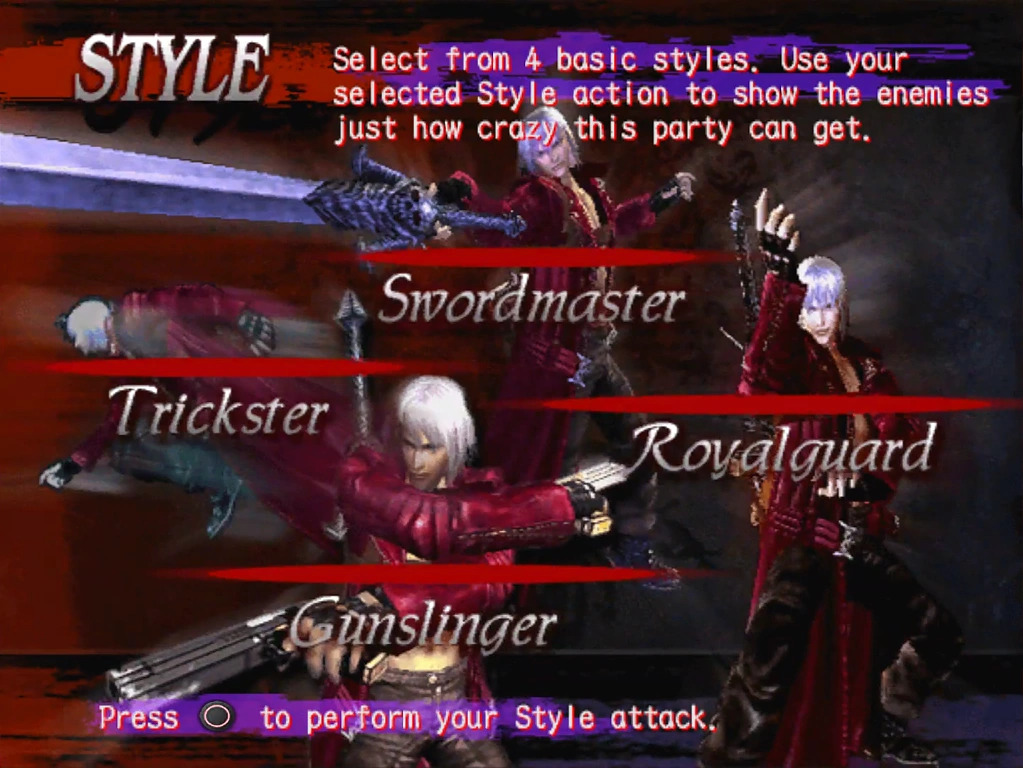

Sporting a youthfuller Dante with a different kind of brass confidence, combat is faster, enemies are more aggressive and areas are smaller once again. Still, a lot of the potential from its second outing is retained. Dante can swap again between ranged weapons with [L2] and melee weapons with [R2], while forcing players to select a loadout at the start of each mission.

At the center of this decision stands the ‘fighting style’ Dante chooses to use that mission. Trickster, Royal Guard, Sword Master and later also Doppelganger and Quicksilver being his options. Ranged, melee, blocking and mobility.

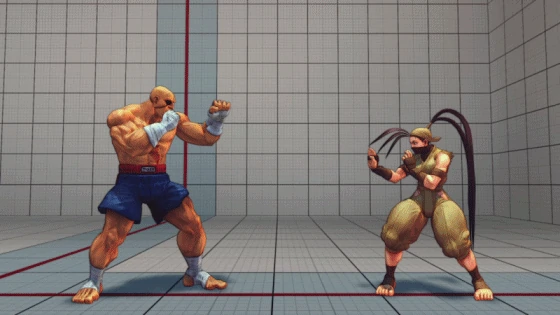

Itusno later explained in interviews that these styles were designed to represent different styles of games. Trickster’s dodge being representative of Devil May Cry 2’s dodge options, Royal Guard’s parry emulating the similarly deep mechanic of Street Fighter III, Sword Master aimed to simulate aerial fighting games like Marvel vs Capcom with its added air combos while Gunslinger allowed Dante to simply “be Dante”. It’s clear here that fighting games are, understandably so due to the director’s history, a big influence and that there was a clear goal to apply fighting game design choices into a traditional action game.

As a result of these combat options that the player has to choose between, enemies are a lot less emphasized, tending to have a more singular focus. Enigmas shoot lasers which can be destroyed, regular enemies rush you down and most can be launched, with no foe having a very specific weakness to a certain weapon or option aside from some of them taking a little bonus damage from specific elemental weapons.

This is understandable, since the designers could never be sure what weapons players would bring into a mission, forcing them to make enemies and bosses more open ended. Some bosses like Cerberus saw this shine, with his “It’s Raining Icicles!” attack being dodgeable with a combination of trickster wallruns, well timed aerial parries or even blocking them entirely using Swordmaster’s Ice Age. It offered a vast amount of player creativity with the plethora of tools available, making it almost strategic.

Conversely, regular enemies are more relegated to being typical foes with a few attacks and mostly being toys to play with than foes to fight. The most interesting enemies are ironically the original 7 sins that have diverse movesets with each a unique quirk like teleportation or aerial attacks.

This is an understandable change though. If we put the two design philosophies side by side,

Devil May Cry under Kamiya’s gaze had its roots in single player arcade games while Devil May Cry under Itsuno’s direction found its roots in fighting games.

This distinction is important going forward as it would slowly shape the series’ future. You can see a shift in how the game balances player and enemy. In the first outing Dante and the enemies were on equal footing in terms of importance, the players actions possible by the enemies and how they functioned. In the third entry this changes to the game being more about what Dante can do, as seen for example in the game’s chess piece enemies. Static enemies that cannot be staggered, but simply do their moves while you do yours. Understandable, as transitioning towards higher player complexity requires more simplified enemies in a sense. If both are equally complex, it risks becoming too complex a whole; a tight balancing act.

It’s a fighting game philosophy where the player character is at the center – since everyone is playing as a player character in the first place and there technically are no enemies.

It wasn’t all changed however, still retaining the original’s mission and secret-mission structure. Some other little nuances also remained, like rolling to dodge, the fixed camera and lock-on to use certain attacks like Stinger; with most players still not using it unless they needed access to a specific move.

With that information laid out, how does this relate to the series as a whole? Let’s grab our now familiar diagram.

We can note that the difficulty has returned while the game’s breadth went down a bit due to there being only one playable character. Mobility is further up due to Dante’s styles giving him abilities like wall running and teleportation but also the way he can play with the environment, more easily use enemy-step to stay in the air and other options like skating on enemies. Meanwhile the enemies are, as noted, more simplified to fit with Dante’s increasing kit.

Some of these changes were supplemented a bit by the later re-release of Devil May Cry 3: Special Edition which made Vergil (who was previously a bossfight) playable. Not only upping the game’s breadth but also making some changes to existing enemies like the Dullahan to be more aggressive and offering the Bloody Palace ‘survival’ mode (originally introduced in Devil May Cry 2) and Turbo Mode, which upped the game speed.

The newly added Vergil sports three weapons that he can change between on the fly and one ranged weapon that he can use even during attacks, while only having a single jump supplemented by a directional teleport. These features make him feel like a more condensed character, though since he mainly uses his boss-attacks and sports some of Dante’s weapons with very similar movesets. Because of this, he can at times also feel like a quick addition rather than a well considered one. That said, Vergil’s inclusion placed a bigger emphasis on the player, not the enemy, by not adding new enemies instead.

Aside from these changes, one lesser known and far more impactful change to the Special Edition was how it increased the frames in which Dante and Vergil could cancel their attacks with a jump, allowing them to at times stay in the air twice as long. It improved mobility and complexity of the characters.

The Nintendo Switch version, which was released more than a decade later, ups this focus on character and complexity even more by allowing Dante to switch styles on the fly while also allowing players to play together in the Bloody Palace as the two brothers.

All in all though, Devil May Cry 3 was a critical success and despite the bad reputation offered by its predecessor leading to poorer sales, it sparked new interest in the series and gave it a future – a second chance not many game series get. Still, it would be 3 years until Devil May Cry saw its next sequel released. In that time one thing did release that impacted the series deeply however: Youtube.

Up until around 2007, challenge runs were large write-ups on Gamefaqs, Devilmaycry.org and Phantombabies, with detailed strategy descriptions. Meanwhile speedruns and cool gaming moments were shared through VHS-tapes uploaded on file-sharing platforms and fansites. Hosting was being supported by passion, like on the old and still active Devil’s Lair.

It was around that time that sites like Youtube and their eastern equiavelents like Youku and NicoNico started to take off – making video sharing a lot easier. The 15 minute time-limit resulted in runs cut into parts, a trend that still continues to this day.

What began as an, almost underground, badly edited VHS clip scene slowly went through a transformative process. Among those were very short clips: style videos. Gamers showing off cool things they were doing in their own room with the games, akin to what Kamiya had envisioned all those years ago. Instead of the style meter however they were finding a different metric to please: commenters.

Style is, at its core, about expressing yourself as an individual. In the case of videogames it allows you to show what type of gamer you are. Some are efficient players, laying waste to an imposing boss in seconds. Others explore player mechanics and enemy AI to create a quasi balet of moves that is more about showcasing the inner workings of the game. Others just want to see how long they can play “the floor is lava”.

Slowly, due to sheer volume, categories started to form. From clips edited together into a ‘combo video’, to more freestyle play, to Tool Assisted runs where the depth of the series was fully laid bare – players were experimenting. All leading up to an event that would be known as “True Style Tournament”, an online event where players could send in their clips to compete with other stylish players on who had the best and coolest tricks. Players would start to make a name for themselves like extremely talented but now sadly deceased Dango (1994-2011†), Dantelink, Brea, Ethereal S, Kail and Pokey – some of which are still active and competing to this very day.

It’s a type of event that continues to this day under the same moniker while others have started their own, like /v/style, ReseteraTrueStyle, Summer Break Away Tournament(SBA), Pride Tournament and many more.

Aside from competing, compilations also started to grow, for example the nearly 20 minute long “Ninja Gaiden, Devil May Cry, God of War Combo video compilation” featuring over a dozen players in celebration of their beloved games.

Where most single player games despite their immense quality would wither over the years, Devil May Cry stayed alive as a result of this scene. New tricks were found, used, reused and repurposed ad nauseum.

Because this kept it alive for so long however, styling would slowly not simply be a part of Devil May Cry, but become it, slowly overtaking the other elements of the game. Before the age of Youtube, when asked on how to play Devil May Cry, players would generally get a few tips with the notion “there is no wrong way to play”. Now, they would get a link to a great video saying “this is how you play”.

Before we look at the fourth entry into the series, it is important to set the stage of 2008. In terms of critical reception and sales, God of War had grown into the giant to beat when it came down to action games. It is no secret that the upcoming God of War III was hotly anticipated, with both Tomunobu Itagaki (of Ninja Gaiden fame) and Hideaki Itsuno himself penning with God of War director Barlog on how excited they were to play it.

With a new generation of consoles around the corner, any series could find a new audience and a fresh start to grow to new heights. And while the third Devil May Cry entry was in a sense made as almost a form of revenge for the second’s failing, the fourth would be a title where the studio could make the series truly their own. One way to do such a thing is with a new protagonist.

It would be a gateway for new players to ease them into the now intimidating world of Devil May Cry, while also allowing for bigger setpieces – with new hero Nero sharing many features of his Greek counterpart; from the larger than life bosses to the semi Quick Time Events done with his corrupted arm.

It would be a bigger game. More enemies, more weapons, more playable characters and – perhaps most intimidating of all – more platforms to be released on. As, unlike prior entries, the upcoming Devil May Cry 4 would release not just on Sony hardware, but also on the Xbox 360 and PC.

There was just one tiny, little, small and insignificant snag….. the budget was the same as before.

Down the line this single issue would lead to time constraints, which would lead to cut content, which in turn lead to reused areas and unfinished movesets. Nero would play through a selection of stages, which Dante would then go through in backwards order, facing the same bosses and enemies along the way.

Combat in Devil May Cry 4, at its most fundamental level, is the same as it was in the third entry. While Nero brings his own more streamlined toolkit to the table, Dante is built for veterans who would love nothing more than to learn.

Nero sports a few unique moves and staples like a charged shot, devil trigger and his unique buster grab. While it doesn’t allow for collision attacks or other more complicated grapple actions as seen in titles like the aforementioned God of War, Dante’s Inferno or The Force Unleashed, it did give a nice twist to the gameplay. In a sense, Nero feels like the essence of the series condensed into a single weapon-moveset.

For Dante, things have changed however. Probably due to time constraints, his styles from Devil May Cry 3 were retained but he can now switch on the fly. Bringing a whole new layer of depth and complexity to his character.

While he originally had to make decisions on what weapons and styles to bring, he now had access to them all. Because of this, a level of overlap started to occur as a lot of Dante’s options and moves prior were made because you might not have brought that other weapon. He could roll, since he might not have Trickster to dodge. The Shotgun could Stinger since you might not have brought a weapon that could do so, etcetera.

“If you could just simply launch cool combos just by repeatedly pressing the same button, then the player wouldn’t feel a part of the action. But by providing him the freedom to using different techniques in the timing of his choice, then the player finally starts to feel that he is cool” – Itsuno

A charged shot still requires you to be in Gunslinger style, which used to mean sacrificing swordmaster’s aerial skill – now it just means you need to press left on the d-pad first. While allowing for extreme creativity and expression, it was a change that would also see Dante’s moveset padded out with a lot of double meanings and filler. It would create the argument that Dante was more complex than he was deep – of which a lengthy discussion could be started by both sides, depending on how they’d interpret those words.

Despite this, the culture that had started with Devil May Cry 3 was kicking back to life. During a dry spell of 3 years, content was wavering and players that had once gone out to style every day were slowly losing interest.

In this case, the rushed development might have actually been a benefit. With a lot of unfinished or unpolished mechanics, Devil May Cry 4 had a lot of what one could call “jank”.

From guardflying and inertia to other mechanics that were born from combining player creativity with the game’s engine quirks. One could argue, in a sense, that the quality of Devil May Cry 4 is not by design, but exists thanks to players who had been conditioned after years of style-play to seek the bottom of the barrel.

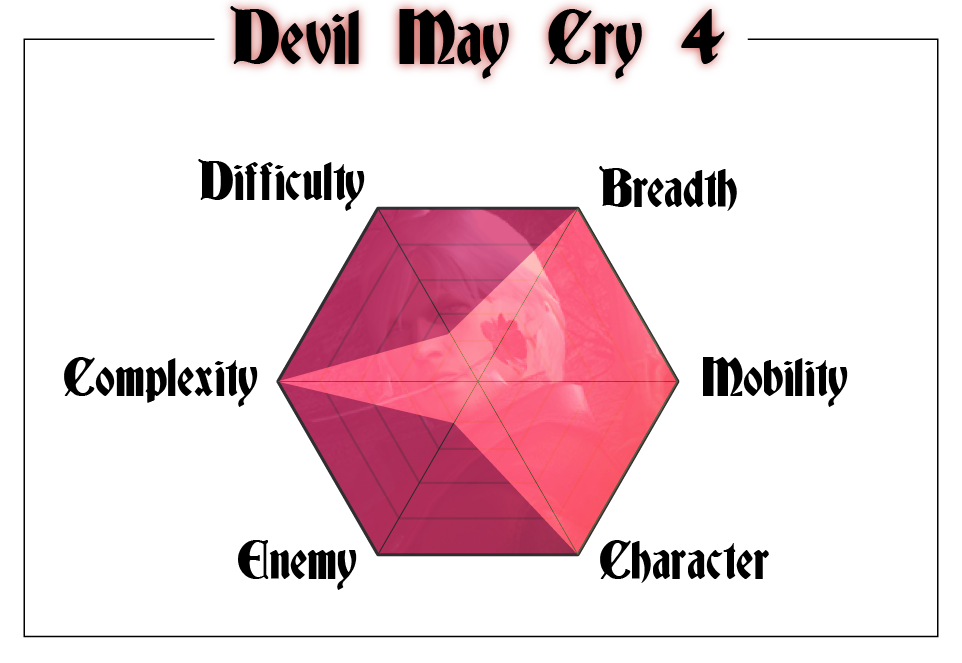

It was with this entry though, and especially its later re-release, that the ‘breadth’ of the series was truly expanded upon. Featuring not just the originally included Dante and Nero, but also Trish, Lady and Vergil as playable characters. The focus was being put more and more on the player character, each with their own unique traits and playstyles.

Trish played more like her Devil May Cry 2 counterpart with a unique twist in her being able to create lines of lightning. Vergil was a souped up iteration of his Devil May Cry 3 release while Lady continued the long standing tradition of Devil May Cry and Sengoku Basara, also a Capcom IP, sharing movesets around. In her case, she took a lot of Magoichi Saika’s moves from Sengoku Basara 4.

Going in depth on each character, their form, function, unique and special tips and tricks, would require an article per character and that is not this article’s goal or intention. Though it should suffice to say that diving into the game’s intricacies is well worth it.

Put together we can see that the series took quite a dive towards one end of the spectrum, putting a much higher emphasis on the playable characters, their complexity, mobility and the sheer amount of playable characters in general. Meanwhile difficulty was lowered significantly while enemies were more passive and had less elements to them; their AI and the manipulation of them mid-combo being the only stand-out feature.

This is not a bad thing. Often titles fall flat because they dare not dedicate to an audience or style of play, and Devil May Cry here makes a firm – if perhaps accidental due to its rushed nature – statement of where it is going.

Once the initial release had passed, most of the challenge runs and high scores had quickly been set, in part thanks to the lower difficulty. Only the now largest, purest, form of fandom remained active: style.

Players like HuangRSfly, JosuaGP and Donguri would push the game forward, just to name a few common names with some new players appearing later or uploading videos one final time due to the constant growth and ease of use of Youtube and its platforms. Meanwhile, others like ChaserTech would focus more on schooling newcomers on how to reach new heights.

There would be plenty of time to reach these new heights as, despite the game’s decent sales, a break was issued and there wouldn’t be a new entry in the series for at least five years.

The original goal of Devil May Cry 4; to appeal to a wider audience, was not met in Capcom’s eyes. Looking at what was included, it had an easier character, more consoles released and even a mobile version called Refrain. It wanted to be bigger but it feared investing in it. So, they would hatch a new plan to expand the serie’s audience.

In came Ninja Theory, a foreign studio led by Tameem Antoniades (pictured above), with the arduous job of inventing a new take on the series. It’s goal? To be more accessible, reach a wider audience and see the series reach this new height.

As a notion, it is understandable. Every individual wants their creation to be loved by all. To be loved by all however means that concessions have to be made. These concessions would lead to the reboot’s tumultuous development. Original concepts got scrapped and the envisioned reimagined series would slowly turn into the familiar formula, even bringing Hideaki Itsuno back on board to help out the struggling studio. Known for their narrative focus, the studio was seeking to bring their own design methods to bear, clashing with Devil May Cry’s arcade roots and also its audience on numerous occasions.

The resulting DMC: Devil May Cry (DmC from here on out) ended up being an action game that played quite like the Devil May Cry 4, but was more accessible while lacking the details of the serie’s combat. It also included more mainstream elements like walking sections, 30 frames per second, no unlockables, pre order DLC, streamlined controls and more.

Initially only featuring a playable Dante and later, through DLC, Vergil, the game featured the least amount of playable characters since Devil May Cry 2. Difficulty was toned down as well, in the attempt at mass market appeal while enemies would only have 1 or 2 attacks at best, serving more as combo fodder. In an attempt to promote weapon usage, the game would have colour-coded enemies at certain points that could only be hurt by certain weapons, an odd choice for a game all about creative freedom.

As such, DmC is far more condensed than prior entries, not peaking in anything, nor fully dismissing any single element.

While many would call out its more popular failings, for instance how you could just shoot pistols from range, how glitchy it was or how insulting the marketing was to fans at some points, one could argue that DmC’s biggest failing was not excelling in any single area of the series when it came to gameplay. It leaves one to wonder if one of the originally scrapped ideas might have been preferable, as they might have at least been unique.

That isn’t to say the game didn’t have merritts. Some of them are minor like how it tried to innovate on the series’ controle scheme, while at other times playing with new difficulty modes like Must Style, where enemies could only be damaged when you were at a certain style-rank.

While the sales were decent. They were below Capcom’s expectations however, and the series would go in a slumber again despite barely having woken up.

In the following years, Devil May Cry’s popularity would flicker on and off from time to time. Re-releases, HD-collections, special and definitive editions on modern hardware bringing a small new audience to bear while giving series veterans an excuse to fire up the old standby one more time.

In the eleven years after Devil May Cry 4’s release the digital age would see a growth however. Gone was the age of 15 minute clips converted from VHS tapes or recorded with their camcorder; the era of fully HD captured footage was becoming the standard. It was supplemented by easy to access capture cards and equipment like Elgato, while gaming companies like Sony would even incorporate capturing and sharing footage in their Playstation 4 console. Add the growth of platforms like Twitch over the old and defunct JustinTV, and what was once an underground scene, was now highly sophisticated and easily accessible.

The easily accessible editing software like Sony Vegas, Premiere Pro and also small competitors like iMovie or online editing software like Youtube’s own studio or InVideo, made editing these clips far easier than before. As such the quality went from old pasted together 240p clips with scanlines and all, to crystal clear 1080p, being well edited with a great timing of music. Every part of the clip was now fully tuned to the experience, with some even featuring their own cover art.

Clips would surface from time to time while other players would stream, but the audience would rise and fall and rise again – never reaching the popularity of larger than life titles such as Minecraft, League of Legends or even Overwatch, but still having a dedicated little community; playing, discovering, experimentation and styling…without end.

Eleven years. Between Devil May Cry 4’s initial release and Devil May Cry V, the gaming landscape saw the release of 11 Call of Duty games, 4 God of War games, the entire rise and fall of the Batman: Arkham game-series and its offspring, 7 Halo games and the revival of the fighting game genre through Street Fighter 4 – just to name a few.

This is also a long time for a game to grow by itself. As noted before, Devil May Cry 3 saw a transition where it would get a clear ‘how to play’ feeling, and Devil May Cry 4 over its nearly 11 year streak saw players learn and grow on an unprecedented scale.

Unintended mechanics that were either glitches or byproducts of the game’s systems were twisted and turned into every possible direction to scrape another month’s worth of experimentation and enjoyment out of the title that kept on giving. In the end it felt like it was wholly part of the game.

So when Devil May Cry V was announced with much fanfare, one question that had to be asked, but none dared to question, was this: had Capcom been watching their players? Did it know how the series had grown and formed in the hands of its players in recent years to see the true strengths?

Some games, even Capcom’s own, have had a history of this. Kara-canceling, a mechanic in Street Fighter, was an unintended byproduct that allowed some characters to cancel the movement of an attack into a grab or another attack, extending their reach. Instead of fixing this, later entries would play into this mechanic.

How would Devil May Cry V, which would continue where the fourth entry left off, handle this in regards to guardflying, inertia and the other more minute aspects of the series that were unknown to the mass consumer? Would it put them to the forefront, or would it go into a bold new direction?

The answer to that would be “neither”. Instead the series would kind of remain where it was. In terms of difficulty, characters, mobility and even breadth of characters it sort of stayed put. Some of the complexer elements were removed, such as the aforementioned inertia, while other little things were finetuned like Dante’s weapon load-out and the content of the game being more streamlined and well designed with less repeat areas. Nero got more combo potential and creativity due to his interchangeable arm while newcomer V brought summoning gameplay back into style, referencing Capcom’s old game Chaos Legion.

V controls differently from Dante and Nero, in that he has buttons that trigger his animal companions to act, while certain other actions like double jumping and dodging summon them to you for an assist. All in all it is an interesting system working within the constraints of the Devil May Cry framework.

In a game though where one character is a grappler which can switch between numerous disposable arm-prosthetic weapons, the other a character with a high focus on mobility and cancelability and the last character being a summoner with a standout playstyle, it is hard to design enemies akin to the ones from the beginning of the series. We’ve seen this part of the games change over the series throughout this article and one can note that it peaks here. While Devil May Cry 4’s enemies could be argued to be designed around Nero specifically; only having them feel as an afterthought for Dante and the other additional characters, in Devil May Cry V it is a design-element at its core. To compensate for the wide cast of characters, the enemies you face are more streamlined and generic in playstyle, including its bosses which at times are just giant targets to wail on and not much else.

Devil May Cry V, as a result, looks eerily similar in diagram form to Devil May Cry 4, albeit a bit less extreme due to its lacking extra content, though the later inclusion of Vergil saw this expanded upon. Enemies suffer because of the breadth of characters as mentioned before and the difficulty only turns its head in the form of bosses being extremely resistant to damage on higher settings, drawing fights out for minutes on end.

Still, these were mostly design elements already present with Devil May Cry 4 as noted, and that didn’t stop that game from living a long life. There was a snag though. The removal of what was handcrafted in Devil May Cry 4’s by its community split said community in a sense. On the one hand they had a game they had personally molded into what it was today, jank and all. It had a feeling of personalisation to it; it was theirs as a whole. Meanwhile Devil May Cry V felt like the streamlined and more finished iteration, while also lacking a bit of that punch that gave its predecessor that staying power.

This split was evident from the very get go, with several players making the jump back to Devil May Cry 4 mere weeks after Devil May Cry V’s launch, while others were determined to push the newest title further and give it the same chance as they did with the previous entries. While the dust eventually settled and players would juggle both games and arguments would calm down, a split wasn’t great.

While its first title was a happy accident, Devil May Cry 2 was a mismanaged problem, Devil May Cry 3 an apology, Devil May Cry 4 a rushed desire, DmC a salvaged idea and Devil May Cry 5 the series trying to live up to its potential. Despite this tumultuous history the series grows on. It is shown both in terms of design and also in sales, with Devil May Cry V slowly outselling the rest of the series, paving the way forward for not just the series but the genre at large.

At the time of writing, the series seems to have hit a stride on which it might settle, with the aforementioned strong sales, favourable critical and fan reception.

Looking through all the diagrams of the games, we can surmise that after Devil May Cry 3 made a bridge between its two directors and their mentalities, the series went less towards the challenging arcade route and more towards becoming a complex action game where the character and player were the star of the show.

“What makes action games fun hasn’t changed in 30 years,” explains Itsuno. “You come up against a challenge, and maybe you don’t beat it the first time, but you know what you did wrong. You know what you’re going to do next time. And you better yourself, you overcome that challenge on your own terms, and by doing that you feel this immense sense of accomplishment. “And I wanted to do that again. I wanted to show the world – hey, don’t you think this is what makes action games fun?”

The original Japanese translation here for the word “challenge” is interesting. It might be more open to interpretation, since difficulty hasn’t been the focus of the series since the third entry. This has been a change that’s been mixed within the series’ fandom. Players looking for a challenge are disappointed by Devil May Cry V’s lack of commitment to that ideal while fans of stylish play seek to mod in older forgotten mechanics or are slowly transferring back to Devil May Cry 4 or other games.

If there’s one thing in all of the above though that the series has done, in all its soul searching, is find its place. While it started out as a simple but deep combat system, it has grown over the years to one that is easy to pick up and enjoy with a grand skill ceiling on a mechanic level, just not the most difficult one to beat. Beating it isn’t the point anymore however, that’s – if anything – just there because it is expected of a game. A remnant of its arcade-roots. That word, “expectation”, let me tell you… it can be a bitch.

Over the years the series still features elements from older games, because they are expected. Dante must Die sees enemies tank damage and foes still hit like a truck, if they manage to land a hit with their low aggression.

Other elements have also been a part of the series since its inception, their inclusion never questioned like the Stinger, Secret Missions and the necessity to buy the Double Jump and limiting its use to certain weapons.

The pitfall with games as such is that they grow but leave in mainstays because “they have been there all along”. You launch enemies by holding back on the stick while pressing Triangle while locking on. Why? Titles like Bayonetta and Metal Gear Rising, to just name a few, had already added in double-tapping inputs to allow these moves when un-locked as well.

Devil May Cry 1 gave jumps i.frames because rolling was too inconsistent for playtesters. Yet, despite Trickster’s inclusion, the roll still exists.

These are just examples to show that, like many other games, the series has built up a lot of baggage over the years; a lot of mechanics that simply carried over because they are staples. Stinger knocks enemies back not because it is an intended mechanic, but because it always did this. The Stylemeter exists not because the game still needs to emulate the feeling of the arcade, but because it was always there.

It is all expected.

It makes for an interesting question that, with the series settling on a formula, is there room for improvement in the current formula, and if so, what is it?

Devil May Cry is currently, for the most part, a game about experimentation and style. Yet players are punished for experimenting through ranks, timers, gated off movelists, through purchases and higher difficulty settings. It isn’t until the credits roll that the player has most of his kit, a concept not foreign to a lot of action games like with Astral Chain infamously gating off its best content until the final chapter’s end.

If we look at the game, what do we see? A mission-based action game with large open areas with numerous fights to use its plethora of mechanics in. And if we look to the more hardcore playerbase? An arena, a single foe, a single character, experimenting, searching, styling.

This offers an interesting question; if Devil May Cry is about style, expression and personalization, why doesn’t the series focus more on those aspects? Why does the game only have a single costume? One has to but look to the mod-pages of the series where the most made and downloaded mods are costumes used to make the game more ‘your own’. Idem for custom backgrounds for their arena, why is the Void – Devil May Cry V’s training area – a single plain field? The desire is clearly there.

And the most controversial one of all; a dream Devil May Cry game that embraces its nature… might forgo the style meter. We’re past the moment where the game itself, through some lines of codes, ranks a player. It is easily circumvented and more something of a neat bonus that’s there since it always has been there. Over the years, players, commentators and viewers have long since replaced the style-gauge. Should they be the judge? Players are able to easily upload clips or livestream these days, allowing other players to watch and rank their performance – bringing the series fully into the digital age.

Embrace what you are as a game, don’t try and have two ends and meet neither. You want to be a hard game? Be a hard game. You want to be a game about style? Be that. And one could argue that that last one has the most merit since we already have hard games. We already have games that do grabs. We already have games that do summoning. We don’t have many games that do what Devil May Cry does however, and do so well despite not even fully committing to the fact.

It is strange to say that these features are slowly making their focused debut in the mobile game Pinnacle of Combat, which seems to forgo traditional levels with a bigger emphasis on style, customization, breadth of characters, short levels and other elements – though sadly through gatcha elements as well, aiming to empty wallets.

It is easy to make remarks like this however – saying that the series should follow its heart and double down. If we go through the achievement numbers, only around 50% of the player base completed Devil May Cry V while only 15% beat the game again on a higher difficulty and only around 3% on the highest setting.

Is that a number you want to risk it all for? Perhaps, perhaps not. That said, hardcore players seem to be getting a bigger focus. An example is director Itsuno and producer Matt Walker watching clips from stylish players.

It is with that, that we can only guess at the series’ future. While, at the time of writing, there is no Devil May Cry 6 announced, it is important to remember one thing when it comes down to this series: Devil May Cry has been around for nearly 20 years. It has been there from the apex of the genre when all sought to copy its success, to a time where its genre was at a low point with only Dante and co. keeping it alive.

Throughout its rocky history it has stayed true to its core tenant; to provide a gameplay-first action title reminiscent of old. As such it is one of the only series around to still do so, and do so successfully. It is easy to focus on the negative in a series so popular and grand, what it could do better or how it could change, etcetera. At the foundation Devil May Cry is a rock solid action gaming series of consistently great quality. It is high quality action, it has been around forever and has a loyal fan base that has kept the games alive for over a decade and will still do so for another, simply out of passion for a title we all cannot help but love.

In a generation filled with more and more scripted story based experiences… to have a game that’s just about the player and the combat, still thrive… is beyond excellent. And should it die out, we can rest assured that it will one day return, like it always does. Dante, until we see you again!

鑒 reflection style 鑒

In this short section I reflect on the article from my own viewpoints as a gamer and lover of the genre instead of a critic.

Originally, the five-year anniversary of Stinger-Magazine would’ve been celebrated with an article on Devil May Cry 1, analyzing it in great detail. Looking to the internet however, so many great analyses already existed, with not a lot to add to them. I briefly considered doing what I did for DOOM; to instead look at what modern designers could take from Devil May Cry, but I felt that wouldn’t do the game’s justice.

In the end, I settled on this, a series wide analysis that would compare and analyze trends between the games, while also inserting some hopes and desires I had for the series going forward.

There’s definitely a lot of things in here that might be controversial, like the suggestion to remove the Style-Meter and the almost handwaving of certain details. While I would’ve loved to write a single article on each and every character and their iteration, well…actually….I did.

Many might not recall, but Stinger started as a simple blogspot site, a page that’s still online funnily enough. There, one of my first projects was to write an extensive rapport on each playable character in Devil May Cry 4: Special Edition, starting with Nero. With a writing quality that, honestly, makes me blush with shame these days, I started and finished the one on Nero, only to stop there, wanting to cover other games instead.

While I’d still love to do this one day, I feel that the site as it stands is getting complex for me to maintain. This article alone took nearly seven months to conceptualize, research, analyze, write, rewrite, edit and format, and to be honest, that’s something I want to take a break from. So expect the next article to be of a much smaller scale.

As a whole though, I’m very pleased with the article as it stands.

Now, about Devil May Cry? It is a series near and dear to my heart, as it is to every fan of the genre most likely. I’ve been stern to it in the past, but only out of a desire to see it grow further. I still recall having problems enjoying the games. Coming from Ninja Gaiden I handled them quite incorrectly. It wasn’t until I saw some of Dango’s videos that the series started to click and I dove in deep, even bringing my PS2 to the office to play during my lunch break.

It is a series that pushed me further as a player and also when it came to discussing these games, always forcing me to bring my A-game and then some. While I admit the older games such as 1 and 3 are still my favourites, it is one of the few remaining series where I’ll still buy a new entry without question. And that alone, to me, is special. Here’s to many more!

斬 postscript notes 斬

- Ironically, when designing Dante, Kamiya envisioned him as someone who was cool. Someone who wasn’t a show-off, but still pulled a ridiculous and mischievous joke to endear people to him. These personality traits have been famously changed over the series, making him in a sense the polar opposite of his original form.

- Kamiya actually has an arcade record in Archives Ninja-Kid’s Caravan mode (158,680), he’s no slouch!

- V always felt out of place to me, almost like a test within an established game, something that’d be it’s own little low budget B-title in the Playstation 2 days, now too risky to develop. Testing the waters.

- Ironically the most care with Vergil seemed to have gone into his implementation of the super-form costume that featured a fully playable Nelo Angelo boss from DMC1.

- I didn’t want to make this article so much about directors, but on the game itself. While vision is important, a game is made by more than just a single individual. Hence why I put a lesser focus on Kamiya and Itsuno as a person, like I erroneously did with Itagaki in the past. Histories surrounding them such as Kamiya’s rising-stardom with Resident Evil 1 and 2, or Itsuno’s vast Fighting Game history, were only passingly mentioned as a result. Similarly, I felt the ‘what inspired’ the series smaller elements such as juggling to be interesting, but not worth dedicating a paragraph too.

- Despite being better in nearly every regard, due to the bad reputation offered by Devil May Cry 2, Devil May Cry 3: Dante’s Awakening only sold around 1,2 million copies compared to 2’s 1,7 million – both a big setback to Devil May Cry 1‘s 2,2 million. This was supplemented a tad by Devil May Cry 3: Special Edition, which sold another million units on the Playstation 2, and another million on PC.

- This is interesting since a lot of devs consider a flopped game to be bad wholesale, but DMC3’s team actually really looked with DMC2 at what worked and what didn’t and expanded on its success and failings. It is rare that a game series gets the turn around that DMC3 gave it.

- In an interview for DMC1, Kamiya mentioned that they would not release information like height, weight, blood type, birthday/place, or anything that related to personal information because it takes away from the mystery of the character.

- When asked about it on twitter, Kamiya confirmed the game was originally made on NORMAL difficulty first, then scaled up. (https://twitter.com/PG_kamiya/status/1365619994013274112)

- Kamiya himself didn’t beat Dante Must Die difficulty.

- Despite wanting to work on his dream game, an action-rpg, director Itsuno helped with DMC2. This dream game later became Dragon’s Dogma.

- Turbo Mode DMC3 wasn’t in the PAL release of SE sadly.

- COMBO MAD became a term that comes from MAD, a Japanese term that came around in the 80s and stands for a variety of things like Movie Anime Doujinshi and Music Anime Douga. It originally stood for fan-made video media. These days MAD doesn’t necessarily refer to just anime content, so if you see a video tagged with the acronym, you can assume it’s video media where content was created by the video creator, as opposed to reused/edited video from other sources.

- Special thanks to the Ultimate Ninja Patrons: Hedfone

源 sources 源

EGM. Inside Devil May Cry. vol. 149, 2001.

Kamiya, Hideki. “Dante Must Die.” Twitter, https://twitter.com/pg_kamiya/status/511097101258723328.Kamiya, Hideki.

“Greetings.” platinumgames.com, 1 april 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20100721220933/http://platinumgames.com/2009/04/01/greetings.

DMC 1 is, by far, my favourite. It’s the one Stylish Action game that has a seriously compelling world, and the Dante Must Die mode is, IMO, the greatest Hard Mode ever made. I love that every mechanic(except Nightmare Beta) is useful. So you not only get the satisfaction of styling, but also of knowing that you’d probably be dead if you didn’t use this specific combo at this specific time. So the mechanics feel valuable and powerful in a way that they don’t in the other games. In this sense, I find it to be deeper as an experience. There is much more meaning packed in to each individual decision I make, including everything from proper Devil Trigger use all the way down to the micro steps I’ll use to reposition myself in battle. Everything is done with intention and purpose and to me, that’s always going to be more satisfying to play. Significantly so!

Dare I say it, but it feels way more expressive to me. I struggle to get that expressive feeling from a game that I’m just bullying. Expression is always in response to something, right? But Itsuno’s games think that expression means that you can just impose yourself on the game, and if I look at my experience and what I know the experience of expression to be, I cannot agree with that. It is not the truth of the matter. It may be counterintuitive, but that’s my experience.

You give me all of these options and make the enemies dumb, and this IMPLIES expression, but I scarcely experience a sense of expression as a result of this. I do like Itsuno’s games, but in the same way that I enjoy messing around in training mode in Street Fighter. And, IMO, when the difficulty does ramp up, it’s almost always difficulty of the annoying kind, in Itsuno’s games.

Personally I like DMC1 and 3 the most, 1 is without a doubt a unique title that hasn’t really been copied since. While 3 really is this kind of ‘all the stars align’ type of action game. I feel that retroactively people have gotten a bit bitter to 3 in a certain regard, in that it started the ‘cuhrayzee’ trend, while it still offers a fantastic combat experience with high difficulty, just like DMC1. Playing well in DMC3, just as 1, requires a great combination of enemy knowledge, combo knowledge etc. otherwise you’re dead (barring exploits ofc. but DMC1 has those too).

It really had hoped that later games would push the envelope further, but DMC4 and 5 aren’t my jam for the reasons you noted (dumb slow enemies that take turns while also being as durable as a tank). I much prefer the difficulty offered in games like NG where both parties are quick to kill and quick to die if you get me.