When an attack hits the enemy, he dies – it should be as simple as that, yet it rarely is. Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, when describing the look and feel of his designs, noted the motto “less is more”. He used only the absolute necessities, with each part of his constructs having multiple uses. It is a proven methodology that is utilized in all manner of crafts, so what about Action Games? With each game we’ve been looking for the depth, the combination of attacks and how it all works in complex ways to motivate us: but what if a game strove to do the opposite. How would that work? Maybe 忍Shinobi for the Playstation 2 is one such game.

As a series, 忍Shinobi has been a long running SEGA franchise. While not as big as Sonic The Hedgehog, it has had nine titles released before Overworks took the series in a new direction, hoping to leave a mark on the newly released Sega Dreamcast. Focusing on a new character and world, this title was to usher in a new era of Action games. Sadly, due to the downfall of the Dreamcast, production was shifted to the Playstation 2 resulting in a delayed release. In the meantime, Devil May Cry would instead make its mark on the genre, leaving 忍Shinobi to finally release one year later in November of 2002, greeted by silence.

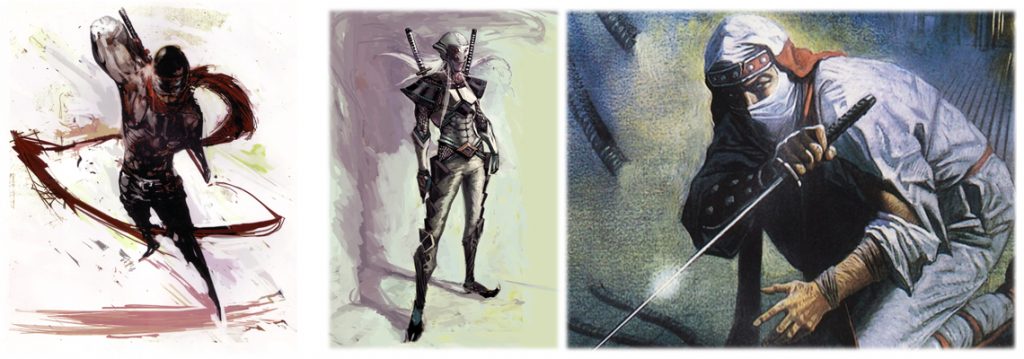

In 忍Shinobi you play as Hotsuma(秀真), a ninja wielding an accursed blade. With a double jump, a dash that leaves mirror images to distract foes and the ability to run along walls, Hotsuma is extremely mobile. When fighting he can slash (攻擊), charge up an attack (集氣), kick enemies to daze them (踢), throw a limited supply of kunai to quickly stun foes (苦無 ), use magical Makimono Scrolls (巻物) and toss out eight kunai at once for an area of effect stun(八個苦無): and those are all the tools and abilities you get. You won’t get any new weapons throughout the game, nor will new attacks be unlocked or improved upon. Combat is, on the surface, very simple.

But complexity isn’t the goal here, as 忍Shinobi is a game with a streamlined approach. Out of range for the kick, you’d have to focus on the limited kunai and vice versa. The kunai also deal minor damage and can destroy locks. You can dodge, but also use its afterimage to distract enemies to attack them from behind for bonus damage. If you dodge to the sides while locked on to an enemy you’ll appear behind them. Hitting an enemy resets your air-dodge capabilities, allowing for tense and long aerial encounters.

The “less is more” mentality is present here in how the options play out. Each move, like the dodge, have more than a single use and exists for a reason. Every option available to Hotsuma is essential to mastering the game. However, in order to do this, the game requires a lot from the player. There is no in-game map displaying where enemies are: you have to remember where they are despite the speed of the combat. Complex save systems and checkpoints are absent: you die during the stage, you go back to the start of the level. There are no upgrade systems: you fight the battle, not Hotsuma. Every option in 忍Shinobi has been carefully weighed against each other and considered with a single question: can player ingenuity replace this, and if not, can this option not be included in the existing options? There is a sort of purity in its gameplay, with the result that it can be an incredibly difficult game.

Talk of purity however, is lost to Hotsuma himself thanks to his blade Akujiki (妖刀「悪食」) constantly lusting for the Yin of lost souls. While playing, a red meter will constantly drain and once it has emptied you’ll start taking damage. Kill an enemy and his Yin will be absorbed into the blade, its hunger sated, if only for a moment. This is where 忍Shinobi’s core mechanic comes to light: the Tate System.

Every fight has a set number of foes and killing an enemy increasing the sword’s damage as it thirsts for more bloodletting. With each subsequent enemy slain you grow stronger, until the final enemy of the encounter is killed or five seconds pass without any bloodshed. Once all enemies in an encounter are killed in a single Tate chain, a short animation plays out and the sword’s power is reset. The animation, aside from being stylish, also allows players a short reprieve from the constant action and a moment to get their bearings. Killing enemies with a full Tate chain also grants extra amounts of Yin, increasing your chance of survival. It, like many elements of the game, is simple as a concept but deep in its execution.

As such, enemies aren’t as much designed around killing you, as they are around blocking your attacks and challenging your Tate chain to fail and have you bleed out. The souls of fallen Oroboro Ninjas gang up on you, Ninken dogs try to keep their armored heads in front of you while Sennin Kunoichi throw kunai to stun you, in the hopes of slowing you down just long enough. Unlike many other Action games, you won’t get hit by massive blows that drain your health by huge chunks, but instead foes slow you down, cut by cut.

Stages operate differently too, instead of being home to exploration or arenas like most Action titles, each stage has a distinct focus. The first is a small maze that teaches the fundamentals of combat and platforming without hefty punishes. The second already introduces floating key stones that need to be destroyed in order to continue. Later stages add more walls to run along than floors to walk on, some are purely vertical, while others are large areas filled with ranged enemies and pits of lava to hinder your progress. The simplistic design of Shinobi translates over to the level’s art-design as well, with each level using simple geometry, re-used textures and models. While the game tries to do its best with the resources it has, it is quickly apparent that the title was on a strict budget.

In a way, its stages are a hybrid of Action, Racing, Platforming and Puzzle genres. This methodology lets the game stay interesting despite the outward appearance of simple gameplay.

Trying to observe the environment, the enemy’s location, certain items you want to pick up and improvising one seamless chain of death while under extreme time pressure and with great speed is 忍Shinobi in a nutshell. You can never sit still and take a breather to take in the surroundings.

This rapid pace is also present during boss battles. While you can cut them with weak attacks and kunai, the real goal quickly becomes apparent when extra enemies appear: you have to kill these minions and use the final most powerful blow from Akujiki to slay the boss in a single stroke. These engagements become a violent dance of you dashing from foe to foe, killing them with the boss breathing down your neck. Then, when only the boss remains and the blade is at its maximum strength, you’ve only got a few seconds to open the towering giant up for the kill, using smart positioning, kicks, kunai or all of the above.

When it works, it is a joy. To end a successful Tate Chain, seeing a boss’s entire life-bar drain in a single blow and cutting everything to pieces is a spectacular sight. Even more-so when you realize bosses all have a few frames of animation in which they take double damage, taunting even the best players. But that’s if it works, and it tends not to more often than not. You may end end your chain too far from the boss, or he’ll be in one of his invincible attack animations, some lasting nearly eight seconds. The further you get in the game, the smaller these openings become.

Some bosses are also immune to stuns, others are hyper aggressive or at times the game just doesn’t want to play ball. While frustrating, it does keep the bosses and stages themselves interesting on subsequent playthroughs. No matter how good you are, a single enemy out of place can throw an entire game-plan upside down, forcing you to quickly adapt or perish.

With such a harsh punishment for death, it is important the mechanics of the game work flawlessly lest the player die to no fault of his own. The camera does a sizable job keeping up, but while wallrunning it tends to lock into place and the turning speed is slower than one would want. Resetting the camera by pressing L1 quickly becomes the default way of orientation as a result. Charging Hotsuma’s sword attack, done by holding down the attack button, can also be annoying as it forces you to first do a regular attack and waiting for Hotsuma to reset his stance while you’re still holding down the button before the attack starts charging. While a workaround exists, namely by pausing the game, holding attack, and unpausing, this is inexcusable in a game where one wrong button input can spell your doom.

Thankfully, the game does show some mercy. For instance there is always a checkpoint before a boss-fight, though this does somewhat ruin the adapt or die mentality. Instead of watching a Tate go up in smoke and waiting for the next perfect opportunity, these fights quickly turn into a player pressing retry if things aren’t going their way. A playstyle that is further promoted by the relatively quick load times.

This approach is further motivated by the scoring system. The game gives out rankings based on the amount of enemies killed, Tate score, how many hits you kill the boss with, the amount of Makimono Scrolls you have left and grants bonus points if you did the whole thing without getting hit. Perform well enough and you get the vaunted S-rank. As a whole, the system motivates you to use the game’s systems, having you kill every enemy using the Tate system, not use magic, complete every single fight and kill the boss in a single stroke, while taunting you to do it all without taking a hit. Strangely enough, the timer doesn’t play into it; a notable omission considering just how badly the game wants to rush players.

This rush is even more amplified on higher difficulty settings. While these settings don’t change enemy encounters, they’re made much more aggressive. Akujiki also drains your Yin nearly twice as fast and bosses have more HP, requiring a full Tate-chain and at times a charged attack in their back to kill them in one hit.

Aside from killing there are also Oroboro Coins to collect, some hidden in devilishly dangerous places with some being exclusive to higher difficulties. Collecting enough of them will unlock things like artwork, a movie gallery and even two new playable characters: Moritsune (守恒) and Joe Musashi (ジョー・ムサシ). Instead of offering different movesets these characters play the same as Hotsuma, but – again – their details are different.

Moritsune’s Yin drains even faster than Hotsuma – fully draining within 20 seconds on the highest difficulty – takes more damage, but brings 250% more pain to his enemies. Musashi on the other hand wields a regular katana and thus doesn’t have to deal with the constant pressure, a trade-off for his lowered damage output. Finally, his kunais are infinite and can damage some bosses that the other characters’ kunai can’t, while lacking the ability to stun.

This change of characters is interesting as it, like many elements of the game, plays into the “less is more” ideology of 忍Shinobi. While the basics remain the same, their subtle changes to mechanics make them feel very different.

With the three characters, multiple difficulty modes and ranks, players can get a huge amount of hours out of this title if they seek mastery. Those looking to procure the highest attainable rank – S-Rank and No Damage on the highest difficulty – with each character are looking at at least 50 to a 100 hours of playtime filled with experimentation, quick reflexes, research, sweat drops, on the fly thinking, intense pressure, platforming, plenty of retries and some glorious kills with a final hidden stage as their reward. Others might be done with the “less is more” approach after one playthrough but will still find a short, but intense little game that tries some new things. 忍Shinobi is a title that shows that “simple” isn’t necessarily bad, but can be an asset to a game that builds around it, showing that it can stand on its gameplay alone and can do without the many additions the genre has gained over the years. That is what 忍Shinobi offers. A unique, deep and also simple title that doesn’t pull any punches.

Less can indeed be more.

鑒 reflection style 鑒

In this short section I reflect on the article from my own viewpoints as a gamer and lover of the genre instead of as a critic.

This is one of those games that just clicks with me on an almost personal level. No matter my mood or the time of day, I can always boot it up have a blast. I think that’s because it is so simple in its methods and inputs, but so deep in the underlying surface. I can always learn something new in a small detail or look at that one foe another way that is eye-opening. The threshold to pick this game up and play it again isn’t that high, unlike some other games that are far more complex. Its sense of style, the music, the way the camera zooms out to show all your kills: the game just oozes entertainment for me and whenever I play it I can’t get enough.

The first time I actually saw this game was in a video of Gametrailers where it was listed as one of the hardest games ever released. While I still find that to be a bit of an overstatement, it is surprising just how much bite the game has on even its easiest difficulty mode. If released today, I honestly wonder how it would be received.

The title does have its downsides for me. When enemies die the game pauses for a second to show you each kill and, while great at first, it gets old fast. Same with having to retry the bosses over and over to get that perfect kill, it feels very much like trial and error at times. The final boss especially deserves a mention considering just how hellish he is, one of the few fights in gaming I truly dread and fear. Lastly, some stages never sat right with me. 3A is a nightmare to do, while 6A’s platforming and orientation just make my head spin, though I do respect the developers for trying to make a completely vertical level. Anyway, there’s a lot to like here, and some things to dislike. One thing’s for sure, no matter how old I am, there’s a good chance I’ll boot up this game again at some point just to feel like a ninja once more. Nothing is as tense, as fast or as satisfying to play as this game…at least for me!

斬 postscript notes 斬

- Ironically, when attending the HKU University of the Arts, one of my teachers once violently noted “no, less is fucking less” when hearing a student make the famous remark to defend his work. This is the first time, nearly a decade later, since that moment that I’ve used the term;

- Despite only selling around 800.000 copies, the game was considered a success and thus spawned a sequel. Kind of hard to imagine in this day and age that such an amount of copies sold could be considered a success. Smart budgeting and knowing your target audience goes a long way;

- Akujiki’s kanji 妖刀「悪食 can be translated to “meat eater” and “evil eater”. The former is a possible reference to a monk that breaks his vow and eats meat – thus a sinner- while the latter translation is pretty obvious;

- Depending on the region of your game, certain functions may differ. Coins will unlock things in different orders and the difficulties are changed. The American version has Normal, Hard and Super difficulties, while the European version adds an Easy mode, while removing Hard and renaming Super to Hard. Contrary to popular belief, European Hard isn’t the same as American Hard, it is the same as the American Super difficulty;

- The game runs at 60 frames per second, and allows NTSC 60hrz even on PAL copies of the game. This is paired with a 480p SD resolution, the game does not (fully) support widescreen. Outside of a single fight there isn’t much lag to be found;

- Probably due to memory limitations, the Japanese voices were removed from the European release in favor of other languages;

- Like many of the action titles of the time, 忍Shinobi’s camera is inverted by default and this cannot be changed;

- With such a simple setup, one could wonder where they’d take the sequel. I’ll leave that up to a future article. Nightshade is a very unique title as well;

- The “less is more” aesthetic can also be found in Hotsuma’s appearance and that of Akujiki. Hotsuma is a generic ninja, but his scarf – a simple red haze – sticks out and leaves a distinct mark on an otherwise bland world. Akujiki is also a very simplistic looking sword;

- The game won 6th place in Gametrailer’s “Top 10 Most Difficult Games”, winning out over Devil May Cry 3: Dante’s Awakening, but losing to Ninja Gaiden;

- The game actually sports quite a nice selection of magical abilities, but it doesn’t promote their use, both in the Tate system and the ranking system. Enemies killed, or even harmed by spells, won’t give points;

- Sadly, because of the way the game is structured, you can skip most of the stages, go directly to the boss and farm the enemies they spawn until you’ve gotten enough Tate points off of them for an easy S-rank, reducing its value. Finally, the ranking system strangely enough doesn’t apply your ranks to a difficulty, but instead to the stage. Beat a stage on Easy with an S-rank, and it will stick despite you getting a C on the hardest setting; making the ranking-screen a bit deceptive;

- This article was remastered for the new website on 22 april 2019 with minor alterations, mostly to structure and better highlighting the issue with the charge-attack input. Another being changing “Sega” into “SEGA”, as it is often written. Strangely I noticed that for the “Sega Dreamcast” the company’s name isn’t written in all caps, ever. Why? No clue;

- Special thanks to my partner in life for supplying the kanji! 謝謝!

源 sources 源

- Story of Art, E.H. Gombrich | ISBN: 9780714832470

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-Mies-van-der-Rohe

- https://gamefaqs.gamespot.com/ps2/561199-忍Shinobi/faqs/36921

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gOcEZPiYuQE

It is precisely because the game looked too simple that I never even gave it a chance, when I look at the gameplay it looks like a mediocre with simplistic mechanics, and thus I never touched it.

I assume this game is like those super hard platformers or maybe like the excellent dustforce in playstyle, atleast that's what I got reading your article.. Need to try it now.

Simple can be excellent, it just has to be done right. It is a lot harder to make a good action game with one attack, than it is to just pump a game full of options and let players just toy around breaking the system. I never played Dustforce, but I know of it (thanks MatthewMythosis). I wouldn't call it akin to that, but close. Shinobi is pretty unique. The platforming really is part of the combat here, and exists to make getting your Tate maxed out harder. Let me know how it is when you try it!

Well put and I feel similar. From the final boss battle to the gameplay it is a painfully entertaining title. When finally collecting the coins required for “Joe” makes one feel like enough hard work can overcome any difficulty have to respect the title for a job well done. The voices and cut scenes from, beginning to end, are high end with a low budget. Really appreciate your take on this…… looking for a HD Remaster or even less likely a complete Remake for PS4. PS5 has a few versions to sell before the system gets “slim” and works properly……lol. Thanks again, great work.

Thanks for the love Bradley, glad you enjoyed it! I really wish Shinobi would make a return in this style. Later games returned to its more classic 2d style, I feel what they did here and with Kunoichi was well worth continuing. The game sort-of got a slight re-release on the PS3 but it is still a basic upscaled PS2 port. Did you also play the game with Joe?